Having moved to the Virgin Islands myself in order to avoid chilly New England winters, I completely understand the draw for snowbirds (winter island residents). There’s a strong connection between St Croix and the New England area. Enjoy a meal at Duggan’s Reef Restaurant with all of the Massachusetts college and university pennants lining the ceiling and listen to owner Frank Duggan’s Boston accent and you’ll feel just like you’re on Cape Cod. Take a sunset sail aboard the Schooner Roseway anchored in St Croix during the winter. If you miss her, you can jump aboard in Boston Harbor where she spends her summers. Bottom line, St Croix is a great place to escape the erratic cold and snow of a New England winter.

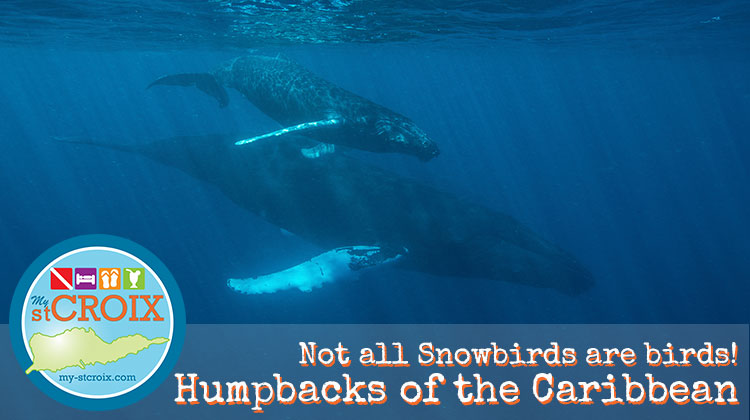

However, these aren’t the only New Englanders who enjoy St Croix’s shores. From about February through mid-April you may also catch a glimpse of some of my favorite “snowbirds”. The migrating Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) whose Latin name translates to “Big winged New Englander”.

Due to the financial and cultural significance of the Humpback to the whaling industry (and it’s subsequent population crash), it is one of the most researched species of whales. Thankfully, due to that research and conservation efforts – including the Endangered Species act of 1973, the population has rebounded in recent decades and the West Indies population is now listed as “Least Threatened” by the IUCN Redlist.

So, other than the balmy weather and swaying palm trees, why do Humpbacks migrate to our waters in the winter months?

These huge marine mammals can measure 52 ft (16 m) long and weigh up to 40 tons with the females being slightly larger than the males. The humpback lifespan is approximately 50 years. Adult humpback whales have about 10 inches of blubber that protects them and keeps them warm in the cold waters of the North Atlantic. Some even do stay during the winter. However, newborn whale calves don’t yet have that protection. So, most of the populations migrates to the tropics in the winter to mate and give birth.

NOAA’s Distinct Population Segments. The blue areas are where the populations mate and give birth (we are #1). The connected green areas represent their summer feeding areas. Source: NOAA Fisheries

However, the warm, clear waters of the Caribbean Sea don’t have the abundance of nutrients that are found in the North Atlantic. Humpback whales are filter feeders who open their huge mouths gulping schools of small crustaceans (mainly krill), small fish and sand eels and then pushing the water out through their baleen. Because of their enormous size, they require tons of those little critters (Literally. They can eat up to 3,000 lbs per day!). The crystal clear waters of the Caribbean, by nature, don’t have that abundance of bite-sized food. So, for their 5-month winter vacation, they eat very little and lose up to 25% of their body mass. The calves are born in the warm waters of the West Indies and once the babies are ready, the families migrate North in the Spring to spend their first summer season eating and growing and eating and growing in order to withstand colder ocean temps. One of their popular feeding grounds is Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary off of the coast of Massachusetts & Maine. Stellwagen Bank is an offshore drop off that creates and upwelling where cold water meets warmer water. These upwellings are rich in nutrients that attract little fish and crustaceans, which attract bigger fish… and marine mammals!

Humpback families in the North Atlantic range in summer from Stellwagen Bank off of the coast of Massachusetts and the Gulf of Maine in the west to Ireland in the east, and up to but not into the pack ice in the north; the northern extent of the humpback’s range includes the Barents Sea, the Greenland Sea, and the Davis Strait, below the Canadian Arctic. Each humpback family always goes back to the same summer feeding grounds – for example, the Stellwagen Bank humpbacks always return home to Stellwagen for the summer; The Greenland families always go back to Greenland. But, they all come down to the West Indies in the winter. This mixing of families during the mating months helps them to maintain genetic diversity and avoid inbreeding.

Here in the Virgin Islands, scuba divers infrequently see them (it does happen for some super lucky folks), but often hear the males singing their intricate songs to attract females for mating. These beautiful songs have been studied extensively and are an incredible form of communication. And because of the low frequency they are sung at underwater, the sound can travel for up to 20 miles. It was Dr. Roger Payne who has studied whales since 1967 that discovered that these songs have a syntax and complex patterns. If you have any interest in learning more about whales, their songs or animal behavior – I highly recommend reading his book “Among Whales” or watch his documentary “A Life Among Whales

“.

Though we don’t have commercial whale watching excursions here on St Croix, they are often seen by boats sailing offshore and can even be seen breaching from land since much of our shelf drops right offshore. One year, boaters off of Buck Island were lucky enough to encounter a female humpback with her baby as they sailed back from a day at the beach. Often in the midst of these once-in-a-lifetime thrills, we forget that these wild animals can be vulnerable too. So, it’s is very important for boaters to note that Humpbacks and other cetaceans (whales and dolphins) are Federally protected from “take” [ Defined by Section 3(18) of the Federal Endangered Species Act: “The term ‘take’ means to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.” ]. Humpback whales can be stressed (harrassed) by extended interaction and there are very clear guidelines that have been established to avoid this.

If you are on a boat that encounters a humpback whale or other cetacean, the captain should observe the following Whale Wise Guidelines:

- SLOW DOWN: reduce speed to less than 7 knots when within 400 metres/yards of the nearest whale. Avoid abrupt course changes.

- DO NOT APPROACH whales from the front or from behind. Always approach and depart whales from the side, moving in a direction parallel to the direction of the whales.

- DO NOT APPROACH or position your vessel closer than 100 metres/yards to any whale.

- If your vessel is not in compliance with the 100 metres/yards approach guideline, place engine in neutral and allow whales to pass.

- LIMIT your viewing time to a recommended maximum of 30 minutes. This will minimize the cumulative impact of many vessels and give consideration to other viewers.

(the above are just a few of the Whale Wise Guidelines. Boaters should review the full list. Another great resource is NOAA’s Stellwagen Whale Watching Guidelines )

Though I’ve been fortunate enough to grow up in New England in a family that is slightly whale watching obsessed, I still haven’t seen one myself here on St Croix. But, when I finally have that incredible experience, I will definitely share it with you!

Many thanks to Dr. Lisamarie Carrubba, NOAA Fisheries & Lia A. Hibbert, Earth Resources Technology, INC. In support of NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program for their input on the Humpbacks of the West Indies!

Have you been whale watching or seen humpbacks in the Caribbean? Let us know about your experience in the comments below!